In moving towards the end of ONL171, the focus was on design for learning in online contexts. Topic 3 of ONL171 focused on learning in communities, specifically ideas around networked and collaborative learning. Among the recommended optional readings was a good overview of communities of practice (Wenger, 2010). A potentially very powerful framework was then introduced for Topic 4, namely Vaughan et al.’s use of Lipman’s (2003) idea of a community of inquiry. Though we learnt about a number of different models, for example Gilly Salmon’s Five Stage Model, on which PBL Group 7 did a thoughtful presentation, CoI seems especially powerful since it offers a good framework for thinking about online and blended learning. As became apparent in the course of taking ONL171 (if it was not apparent before!), building community is essential for online learning. The CoI framework suggests that one needs to work at fostering a CoI through social, cognitive, and teaching presence, and suggests ways of doing so through deliberate design decisions so as to ensure that such a community be established and sustained through a learning environment of trust (“social presence”), which would foster sustained reflection and discourse (“cognitive presence”), and provide direction and cohesion to the learning community (“teaching presence”) (Vaughan et al., 2013, p.12). This conceptual framework also suggests some key principles for operationalising the framework, updated from Chickering and Gamson’s 7 tried and trusted principles of good practice in undergraduate education (1987), in order to take account of the changed learning environments that characterise learning today:

While these principles have served higher education well in directing attention to good teaching and learning practice, we believe that these principles need to be updated to address the changing needs in higher education to become information literate in the age of the Internet. These principles must be consistent with the ubiquitous connectivity afforded students today.

A key aspect of the CoI approach is that of shared responsibility: “The pioneering innovation of virtual communication and community requires both teacher and student to engage, interact, and contribute to learning in new ways” (Vaughan et al., 2013, p.14). This is in part achieved by means of a “joint enterprise”: a common project that needs to move towards resolution, which very much reminds me of the idea of communities of practice (CoP). The CoP model presents a powerful framework for thinking about learning organizations: i.e., “groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise” (Wenger & Snyder, 2000, p.139). CoP is essential for thinking about learning and teaching in universities and other educational institutions and has been used extensively for considering how academic developers can support and foster enhancement in higher education (Mårtensson & Roxå, 2016, 178-179), highlighting among other things the importance of:

- collegial conversation about learning and teaching, in particular informal conversation (also Roxå & Mårtensson, 2009);

- a sensitivity to the local contexts of academics–in particular their orientation towards other dimensions of their academic practice, most especially research: i.e., the CoPs that are already in place;

- shared learning projects, which help constitute the joint enterprise by deepening the mutual commitment of members and thereby push their practice further by fostering connections within the community

- such projects require a rhythm of regular engagement as well as concrete (“reified”) artefacts that result from the work and document it so the work can benefit the community.

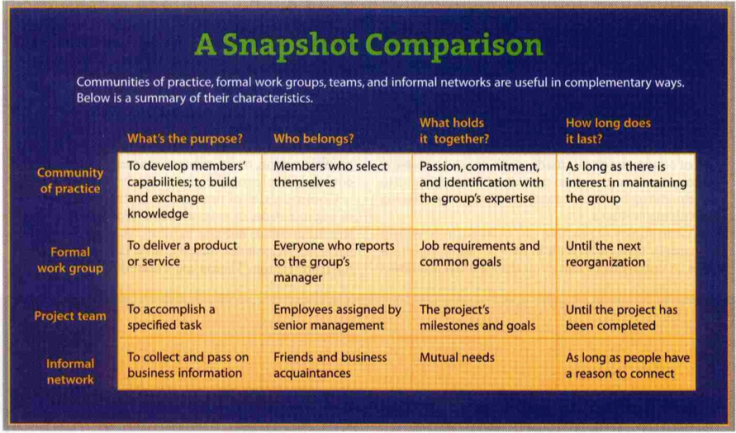

It seems to me that, in view of the above points, CoP is in principle very relevant also for online learning of the sort that we have engaged in over the last weeks in ONL171. It is possible to distinguish between CoPS and other forms of organization, as below:

(Wenger & Snyder, 2000, p. 142)

How does CoI fit into this picture? Given that both CoP and CoI emphasise communities for learning, I wonder how they relate to each other. The notion of CoP did not evolve specifically in relation to online or blended learning, so what are the key difference and similarities between these CoP theory and the CoI framework? To what extent are they compatible, and can each learn from the other? How can we use the important insights of both to take an effective and efficient approach to academic development? This is a question that I would like to explore further, in particular with regard to what seems to me one of the key strengths of CoP theory, namely that CoPs can become self-sustaining if cultivated in appropriate ways (Mårtensson & Roxå, 2016). Given the ephemeral nature of online communities, which seems part and partial of their virtual character, what what can we learn from this theory to strengthen CoIs so that they persist, survive, and indeed thrive?

References

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education. American Association for Higher Education Bulletin, 39 (March), 3–7.

Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mårtensson, K., & Roxå, T. (2016). Working with networks, microcultures and communities. In D. Baume & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 174–187). London: Routledge.

Roxå, T. & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks – exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547-559. DOI: 10.1080/03075070802597200.

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Edmonton: AU Press.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179-198). London: Springer.

Wenger, E. & Snyder, W. (2000). Communities of practice: The social frontier. Harvard Business Review (January-February).